Text & Photos: Mai-Britt Berghöfer, Lotta Bergfeld, Ludovica Gatti, Diana Monroy

Die Meteor ist nun schon seit über drei Wochen unser zu Hause und das letzte Mal, dass wir Land gesehen haben, waren die Kanaren. Der morgendliche Blick auf das unendliche Blau ist Alltag geworden und für die meisten Landratten unter uns ist es die längste Zeit am Stück auf See. Doch mittlerweile sind wir alle an das Leben auf der See angepasst. Wenn es Eis zum Nachtisch gibt, wissen wir, es ist Donnerstag oder Sonntag. Und wenn es Suppe gibt, ist Samstag. Keiner erschrickt mehr, wenn kurz nach dem Mittagessen um 12:00 BZ das Typhon der Meteor erklingt, und wir wissen, es ist 10:30 Uhr UTC, wenn ein Wetterballon in die Luft steigt.

Der Wetterballon samt Radiosonde wird von der Forschungsgruppe der Universität Potsdam und vom Bordwettertechniker des Deutschen Wetterdienstes (DWD) gestartet. Mit Hilfe dieser Radiosonden kann man bis in eine Höhe von 24 km über dem Meeresspiegel die relative Luftfeuchte, die Temperatur und die Windrichtung und -geschwindigkeit bestimmen. Diese Parameter helfen unter anderem dabei zu verstehen, ob die Voraussetzungen für Gewitter gegeben sind oder nicht.

Wir sind an Konvektionsmustern und insbesondere an Wechselwirkungen zwischen Konvektion und der Wasseroberfläche interessiert. Dafür schauen wir uns neben der Schichtung der Atmosphäre auch die Meeresoberflächentemperatur und ihre Sensitivität gegenüber Änderungen in der einkommenden Strahlung an.

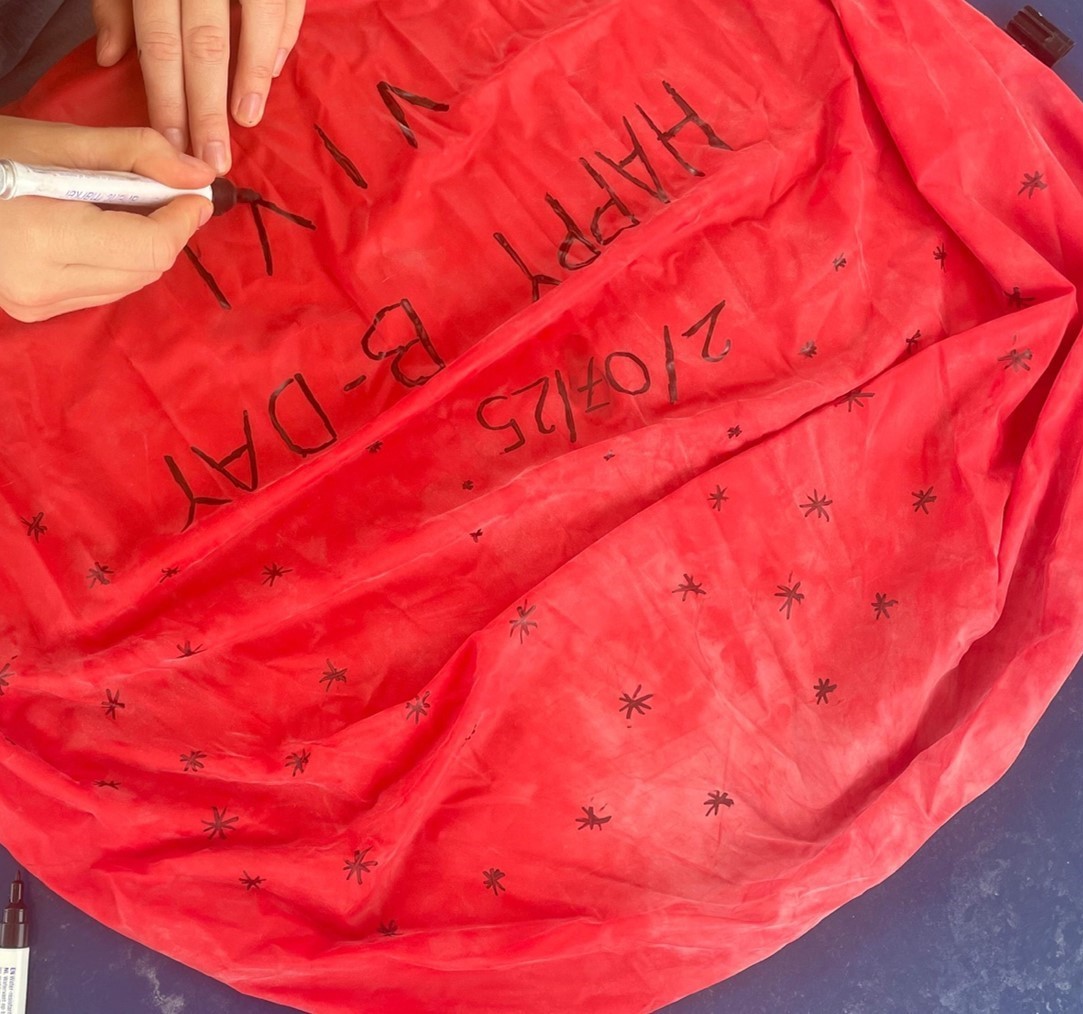

Die Ballons sind mit Helium gefüllt und zum Zeitpunkt des Starts ungefähr 1,30 m breit. Weil der Luftdruck mit zunehmender Höhe abnimmt, dehnt sich der Ballon immer weiter aus, bis er am Ende seiner Reise platzt. Wie weit er reist, hängt ganz davon ab, wie windig es ist. An besonderen Tagen transportiert der Ballon für uns auch eine Botschaft, bis in die Stratosphäre.

Normalerweise werden die Ballons an den Wetterstationen des DWD zu den synoptischen Kernzeiten gestartet: 0, 6, 12 und 18 Uhr UTC. Die von den Radiosonden übermittelten Daten werden im Anschluss unter anderem dafür genutzt, die Wettervorhersage zu verbessern. Wir sind auf dieser Reise jedoch flexibler, um auch außerhalb dieser Kernzeiten die Stabilität der atmosphärischen Schichtung zu bestimmen, und haben zusätzliche Wetterballons dabei.

Mit den Extra-Ballons können wir prüfen, ob die Bedingungen für Konvektion in der Atmosphäre gegeben sind. Wir sind besonders gespannt auf die letzten Stationen, ganz nah am Äquator. Dort in der Innertropischen Konvergenzzone (ITCZ) sind die Voraussetzungen für Konvektion perfekt: Hohe Luftfeuchtigkeit und viel Wärme sind der Motor für Gewitter.

There is no such thing as bad weather, there is only convection

The Meteor has been our home for over three weeks now and the last time we saw land were the Canary Islands. The morning view of the infinite blue has become part of everyday life and for most of us landlubbers it is the longest time at sea in a row. But by now we have all adapted to life at sea. If there is ice cream for dessert, we know it is Thursday or Sunday. And if there is soup, it is Saturday. Nobody is surprised anymore when the Meteor horn sounds shortly after lunch at 12:00 LT, and we know it is 10:30 o’clock UTC when a weather balloon rises into the air.

The weather balloons and radiosondes are launched by the research group from the University of Potsdam and the weather technician of the German Weather Service (DWD) on board. With the help of these radiosondes, the relative humidity, temperature and wind direction as well as the wind speed can be determined up to a height of 24 kilometres above sea level. Among other things, these parameters help to understand whether the conditions for thunderstorms are present or not.

We are interested in convection patterns and particularly in interactions between convection and the water surface. In addition to the vertical profile of the atmosphere, we also look at the sea surface temperature and its sensitivity to changes in the incoming radiation.

The balloons are filled with helium and are approximately 1.30 metres wide at the time of launch. As the air pressure decreases with increasing height, the balloon expands further and further until it bursts at the end of its journey. How far it travels depends entirely on how windy it is. On special days, the balloon also carries a message for us, right up into the stratosphere.

Normally, the balloons are launched at the DWD weather stations at the synoptic core times: 0, 6, 12 and 18 o’clock UTC. The data transmitted by the radiosondes is then used to improve the weather forecast, among other things. However, on this trip we are more flexible and can investigate the atmospheric stratification outside of the core times, since we have additional weather balloons with us. With the extra balloons, we can check if the conditions for convection in the atmosphere are present. We are particularly excited about the last stations, very close to the equator. There, in the Inter Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), the conditions for convection are perfect: high humidity and a lot of heat are fuel for thunderstorms