Text & Photos: Mira Kehr & Martin Pöppelreiter

Durch die Straße von Gibraltar und vorbei an den Kanarischen Inseln haben wir nach erfolgreichem Passieren der ersten beiden Stationen nun eine weitere Transitphase erreicht. Während des ersten Transits hielten Vertreter:innen aller Arbeitsgruppen an Bord wissenschaftliche Vorträge über ihre Arbeit. Dabei präsentierten sie ein Gesamtbild ihrer aktuellen Forschung, welche Proben und Daten sie während der Expedition sammeln wollen, in welchem Kontext diese untersucht werden und welche Fragestellungen beantwortet werden sollen.

So konnte sich ein gemeinsames Verständnis des Gesamtkonzeptes entwickeln – jeder an Bord hat nun einen guten Überblick. Dies ist besonders hilfreich bei der Koordination der Arbeitsabläufe an den Stationen, an denen genau geplant werden muss, wer welche Proben und Daten woher, wann und wie benötigt. Diese Tage müssen streng getaktet sein, um in der knappen Zeit das meiste herausfinden zu können.

Meistens auf dem Deck oder im angrenzenden Labor ist die Arbeitsgruppe Prozesse und Sensorik Mariner Grenzflächen des ICBMs anzutreffen. Ein ‚selbstgebauter‘ und selbstfahrender Forschungskatamaran, liebevoll getauft ‚Halobates‘, ist das Herzstück der Expedition. Er ist benannt nach dem Wasserläufer, der sein Leben an der Meeresoberfläche verbringt und sammelt auf der M211 Expedition kontinuierlich Wasserproben und Messdaten.

Die Stationstage begannen für unsere Arbeitsgruppe in der Regel vor Sonnenaufgang. Bis zum Sonnenuntergang wurde Wache gehalten, mit dem Schlauchboot die Proben von Halobates eingesammelt und Drifter der Arbeitsgruppe Marine Sensorsysteme des ICBMs und vom LOCEAN (Laboratoire d‘ Océanographie et du Climat) ausgesetzt. Später werden diese nach – mal längerer und mal kürzerer Suche – wieder an Bord ‚gefischt‘. Kurz vor Einbruch der Dunkelheit wurde auch Halobates wieder an Deck geholt und die gesammelten Daten ausgewertet. Zu guter Letzt wurden abends die nächsten Arbeitsschritte und -schichten geplant.

Parallel wurde weiter an zusätzlichen Funktionen für den Katamaran gefeilt und gebastelt, etwa an einem Telemetrie-System oder einer Winde, mit der ein CTD-Sensor bis in zehn Meter Tiefe herabgelassen wird und Leitfähigkeit, Temperatur und Tiefe misst. Erste Tests verliefen vielversprechend, aber das finale System braucht noch etwas Entwicklung.

Geht man an Deck nach rechts, vorbei am Geologie-Labor und ins nächste Labor, trifft man neben den Teams der Marinen Sensorsysteme auf das Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon aus Geesthacht. Dort wird mithilfe der FlowCam Plankton aus verschiedenen Meerestiefen analysiert. Am Aqualogger wird fluoreszierende, gelöste organische Substanz (FDOM) aus dem Oberflächenfilm und dem darunterliegenden Wasser quantifiziert.

Obwohl es ungeahnte Probleme mit dem FDOM-Datenloggern auf Halobates gab, wurde schnell an einer alternativen Lösung zur Datenspeicherung gearbeitet. Darum geht es viel auf Forschungsausfahrten – schnell mit dem, was an Bord ist, Lösungen für die kleinen und großen Herausforderungen des Alltages zu finden. Auch das Bio-Optical Package, gerne BOP genannt, wird regelmäßig mit dem Marine Sensorsysteme-Team eingesetzt. Kranzschöpfer mit CTD-Sensoren werden, sobald die METEOR in stabiler Lage ist, möglichst alle zwei Stunden bis zu 600m heruntergelassen.

Im Geologie-Labor trifft man außerdem auf das Team der Klimaphysik der Universität Potsdam. Sie können zum ersten Mal oberflächennahe Daten direkt in ihre numerischen Simulationen einfließen lassen – dank der Infrarot-Wärmekameras, die auf Halobates installiert wurden.

Verlässt man das Geologie-Labor, geht den Gang hinunter und biegt nach links ab, trifft man auf die Mikrobiologin:innen des ICBMs. Trotz der hohen Anforderungen an Wasserprobenvolumina von Halobates zeigen sie sich zufrieden. Sie arbeiten konstant daran, möglichst große Mengen an Proben zu filtrieren und einzufrieren, um diese später in Oldenburg auszuwerten. Ziel ist es, mikrobielle Gemeinschaften an der Meeresoberfläche und ihre Wechselwirkungen zu entschlüsseln.

Hoch oben auf dem ‚Heli-Deck‘ (Helikopter-Deck) sind die Atmosphärenphysiker der Universitäten von Colorado und Alabama-Huntsville zu finden. Sie führen regelmäßig Drohnenflüge durch, bei denen die Geräte bis zum Wolkenboden aufsteigen, atmosphärische Profile erstellen und anschließend wieder sicher am Startpunt landen.

Folgt man den Schläuchen vom Heli-Deck aus nach unten bis ins Labor der Grenzflächenanalytik begegnet man Chaoyang Xue mit seinem Spurengas-Sampler des Max-Planck-Instituts für Chemie. Zusätzlich wird das Flowthrough-System der METEOR genutzt, um Daten zu erfassen, die zur Quantifizierung des Spurengasaustauschs zwischen Atmosphäre und Ozean herangezogen werden.

Auf die Crew der METEOR ist hierbei in allen erdenklichen Lagen Verlass. Selbst bei hohem Wellengang und schwierigen Bedingungen auf dem Schlauchboot bringen die Erfahrenen Mensch und Gerät – ohne allzu viele Sprünge über Wellenberge – wieder sicher an Bord. Gerade auf dem Schlauchboot merken sowohl Wissenschaftler:innen als auch Crewmitglieder:innen jedoch auch, dass Seekrankheit auf dem offenen Ozean dazugehört.

Auch eine Führung durch den Maschinenraum mit dem leitenden Ingenieur wurde angeboten und war natürlich gut besucht. Und in der Messe übertrifft sich das Küchenteam tagtäglich: Niemand „aus der Wissenschaft“ wird wohl jemals wieder so lange am Stück so gut essen wie hier an Bord. Geburtstagslieder, schärfste Chili-Saucen und sogar Schnecken waren auch schon Teil der Reise.

Und natürlich: kein Tag ohne den Wetterbericht des Deutschen Wetterdienstes, kurz DWD: Jeden Tag um 11:30 Uhr werden rote Wetterballons gestartet, die Atmosphärenprofile erfassen und zu Vorhersagen beitragen. Das freut natürlich besonders die Kolleg:innen aus Potsdam.

Aktuell liegen die Temperaturen in den niedrigen 20ern, leichte Brise, gute Sicht, viel Sonne und kaum ein vereinzelter Tropfen von oben. Das ginge sicher auch als erhöhte Luftfeuchtigkeit durch.

English Version:

Status update from Monday, July 1, 2025 (Day 16 of 41 on the M211 “Fresh Ocean” expedition)

After passing through the Strait of Gibraltar and past the Canary Islands, we have now entered another transit phase following the successful completion of our first two stations. During the initial transit, representatives from all the scientific working groups on board gave presentations about their research. They outlined the overall scope of their current projects, what samples and data they aim to collect during the expedition, in what context these will be analyzed, and which research questions they hope to answer.

This created a shared understanding of the expedition’s overarching concept—everyone on board now has a good overview. That’s particularly helpful when coordinating work at the individual stations, where it must be carefully planned who needs which samples and data, from where, when, and how. These days must be tightly scheduled to make the most out of the limited time.

Usually found on deck or in the adjacent lab is the working group ‘Processes and Sensing of Marine Interfaces’ of the ICBM. At the heart of the expedition is a self-built, autonomous research catamaran, tenderly named Halobates—after the water strider that lives its entire life at the sea surface. On expedition M211, Halobates continuously collects data and samples from the Sea Surface Microlayer and the underlying bulk water.

For our group, station days began before sunrise. Watches were kept until sunset, samples were collected by dinghy, and drifters from the Marine Sensor Systems group (ICBM) and LOCEAN (Laboratoire d’Océanographie et du Climat) were deployed and – after a short or a long recovery time – later “fished” back in. Shortly before nightfall, Halobates was retrieved to deck and the collected data were processed. In the evenings, the next steps and watch schedules were planned.

In parallel, work continued on additional technical features for the research catamaran, such as a telemetry system and a winch to lower a CTD sensor down to ten meters measuring conductivity, temperature, and depth. The first test runs were promising, though the final system still needs some development.

Heading right on deck, past the geology lab and into the next lab, you’ll find the teams from Marine Sensor Systems and the Helmholtz Centre Hereon from Geesthacht. Using the FlowCam, they analyze plankton collected from various ocean depths. At the Aqualogger, fluorescent dissolved organic matter (FDOM) is quantified from the sea surface film and the water just beneath.

Although unexpected problems arose with the FDOM data loggers on Halobates, an alternative data storage method was developed quickly. That’s a big part of research cruises: finding fast, on-board solutions for both the small and the big technical challenges that arise.

The Bio-Optical Package—affectionately known as “BOP”—is also deployed regularly with the Marine Sensorsysteme-Team. CTD rosettes are lowered as often as possible from the ship down to about 600m —ideally every two hours—whenever the METEOR is in a stable position.

Back in the geology lab, you’ll also meet the climate physics team from the University of Potsdam. For the first time, they’re able to incorporate near-surface data directly into their numerical simulations—thanks to the infrared cameras mounted on Halobates.

Leaving the geology lab, heading down the corridor and turning left, you’ll find the microbial oceanography experts from the ICBM. Despite demanding water volume requirements, they’re satisfied with the probes sampled with Halobates. They work eagerly to filter and freeze as much sample volume as possible to analyze it back in Oldenburg. Their goal: to decipher microbial communities at the ocean surface and their interactions.

High up on the so called ‘heli-deck’ (helicopter deck) are the atmospheric physicists from the University of Colorado and the University of Alabama–Huntsville. They regularly launch drones that ascend to the clouds’ base, measure atmospheric profiles, and then return safely to their launch site.

Following the tubes running down from the heli-deck to the Marine Interfaces lab, you’ll find Chaoyang Xue operating the trace gas sampler from the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry. The METEOR’s flowthrough system is also used to collect data for quantifying gas exchange between ocean and atmosphere.

In all conditions, the METEOR’s crew proves to be reliable in any situation. Even in rough seas, experienced boat operators bring scientists and equipment back safely in the dinghy—usually without too many jumps over the wave crests. However, on the dinghy, both scientists and crew members were also reminded that seasickness is, unfortunately, an inherent feature of research cruises on the open ocean.

A tour of the engine room with the chief engineer was also offered and, unsurprisingly, well attended. And in the galley, the kitchen team continues to outdo themselves every day—no one “from science” will likely eat this well for this long ever again. We’ve had birthday songs, the spiciest chili sauces, and even escargot.

And of course, no day is complete without the weather report from the German Weather Service (DWD): every day at 11:30 a.m., red weather balloons are released to collect atmospheric profiles that feed into forecasting models. That is particularly important for the colleagues from the University of Potsdam.

Currently, temperatures hover in the low 20s Celsius, there’s a light breeze, good visibility, plenty of sun, and only the occasional drop from above—arguably more like increased humidity than actual rain…

Fotos:

1: Besprechung der CTD, die gleich ins Wasser gelassen wird // Discussion on the CTD that is about to be lowered in the water

2: Sichttiefenbestimmung mit der Secchi-Scheibe // Determination of Secchi Depth

3: Der autonome Forschungskatamaran Halobates in ungewöhnlich ruhigen Gewässern // The Autonomous Surface Vehicle (ASV) Halobates in surprisingly calm conditions

4: Surrende Drohnen überm Deck // Buzzing Drohnes over Deck

5: „Ahh I seee!“

6: Halobates mit voller Geschwindigkeit in Richtung Meteor // Halobates with full speed towards the Meteor

7: Im Schlauchboot auf dem Weg um Proben von Halobates an bord zu bringen // on the way to collecting samples from Halobates with the dinghy

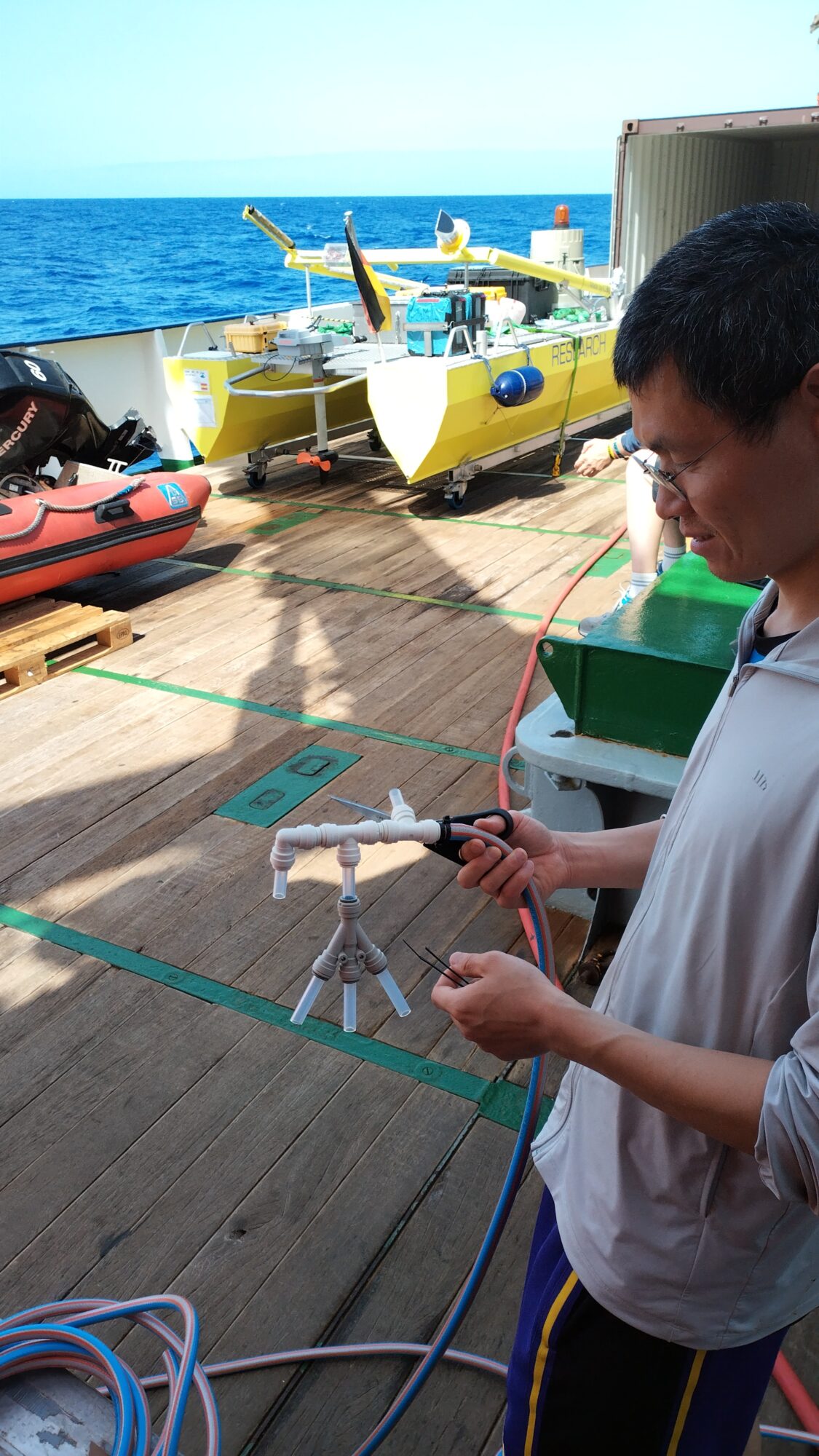

8: Neue Schläuche für den Spurengas-Sampler // New tube set for the Tracegas Sampler

9: Ungewöhnliche Signale bei der CTD // Unusual signals from the CTD

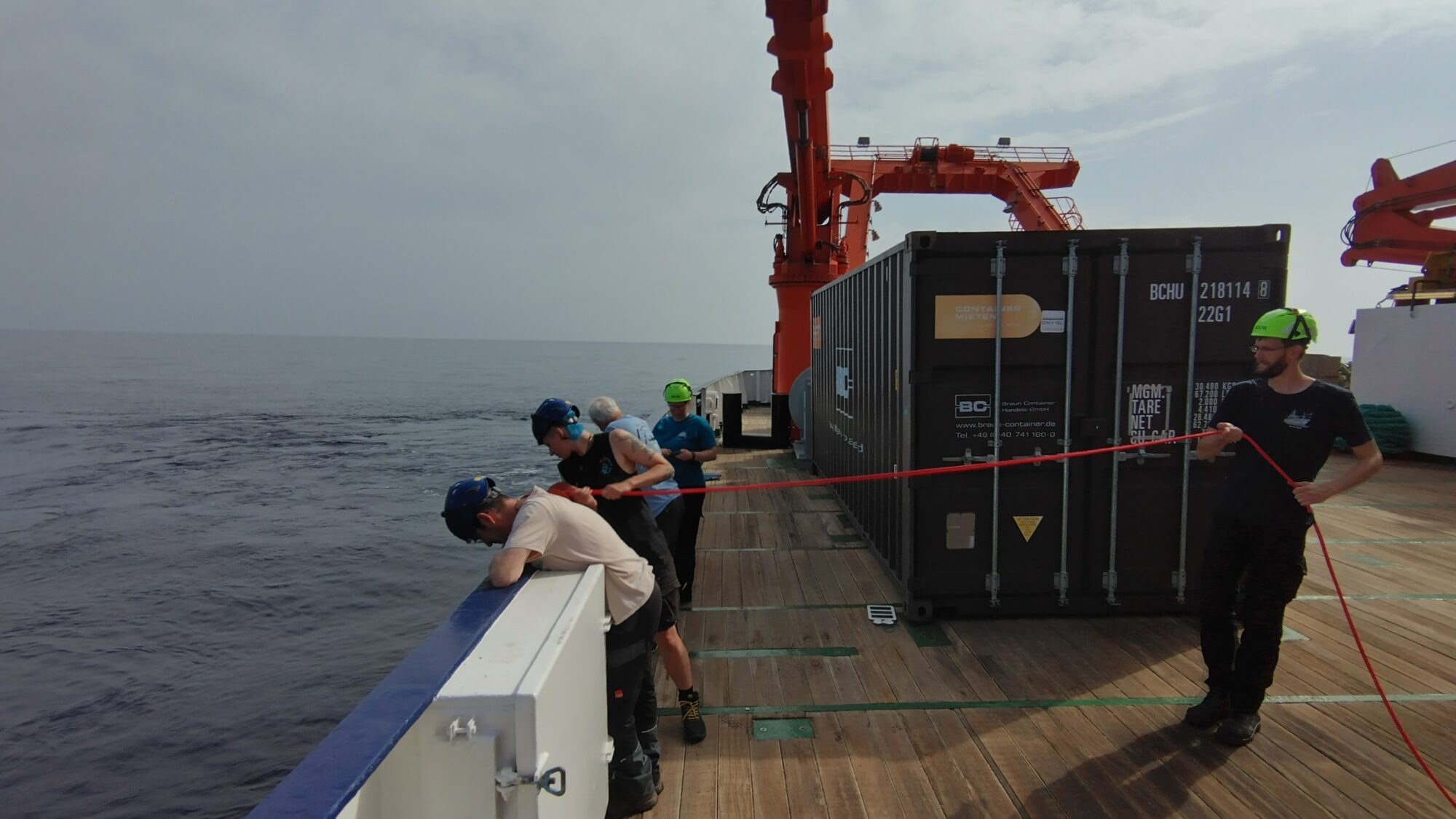

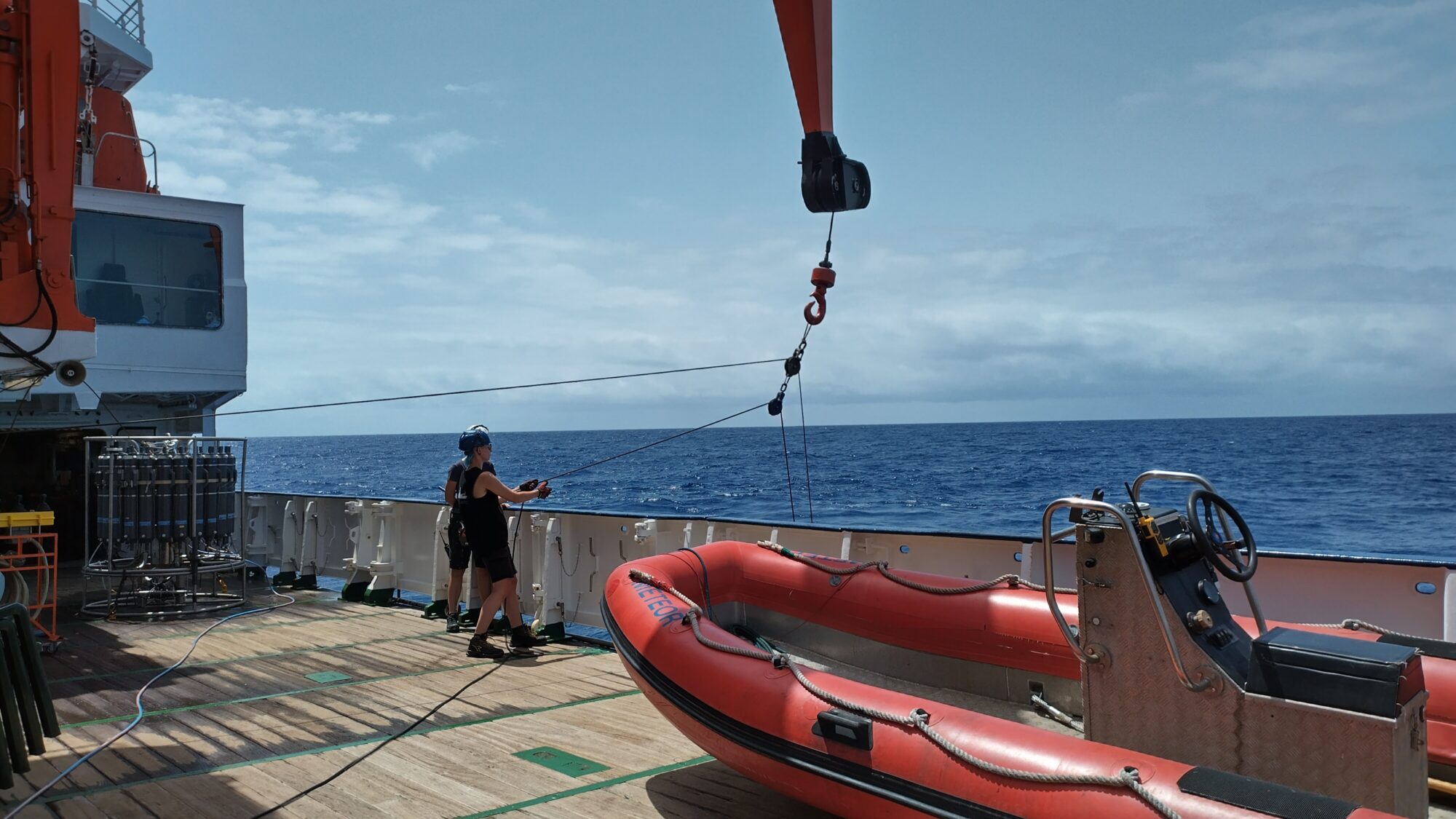

10: Hieven des Bio-Optical Packages zurück an Bord // Hoisting the Bio-Optical Package back on deck